Normally, when someone sends feedback like this, I ignore it, but it happens often enough that it deserves an explainer, because the answer is really, really simple. So simple, in fact, that it should be evident to the likes of Bruce, who decided his misunderstanding deserved a 1-star Trustpilot review yesterday:

Now, frankly, Trustpilot is a pretty questionable source of real-world, quality reviews anyway, but the same feedback has come through other channels enough times that let’s just sort this out once and for all. It all begins with one simple question:

What is an Email Address?

You think you know – and Bruce thinks he knows – but you might both be wrong. To explain the answer to the question, we need to start with how HIBP ingests data, and that really is pretty simple: someone sends us a breach (which is typically just text files of data), and we run the open source Email Address Extractor tool over it, which then dumps all the unique addresses into a file. That file is then uploaded into the system, where the addresses are then searchable.

The logic for how we extract addresses is all in that Github repository, but in simple terms, it boils down to this:

- There must be an @ symbol

- There can be up to 64 characters before it (the alias)

- There can be up to 255 characters after it (the domain)

- The domain must contain a period

- The domain must also have a valid TLD

- A few other little criteria that are all documented in the public repo

That is all! We can’t then tell if there’s an actual mailbox behind the address, as that would require massive per-address processing, for example, sending an email to each one and seeing if it bounces. Can you imagine doing that 7 billion times?! That’s the number of unique addresses in HIBP, and clearly, it’s impossible. So, that means all the following were parsed as being valid and loaded into HIBP (deep links to the search result):

- test@example.com

- _test@google.com

- fuckingwasteoftime@foo.com

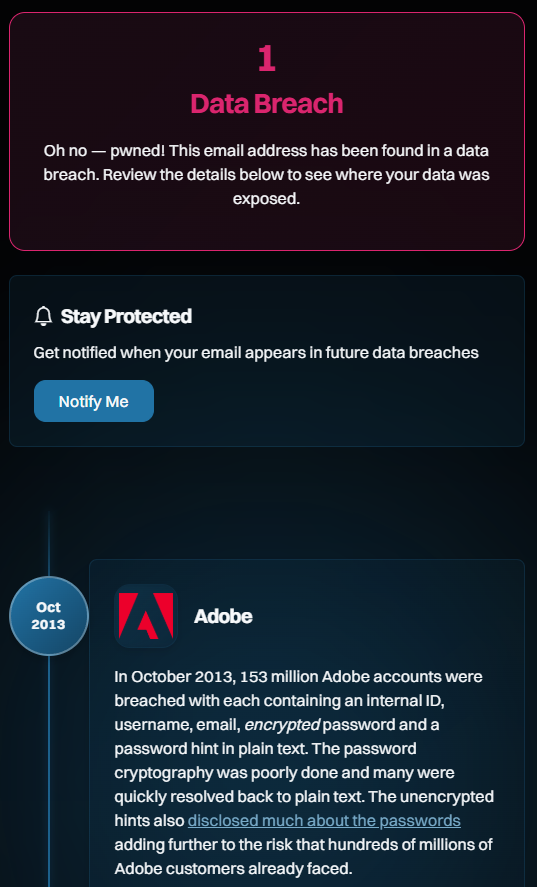

I particularly like that last one, as it feels like a sentiment Bruce would express. It’s also a great example as it’s clearly not “real”; the alias is a bit of a giveaway, as is the domain (“foo” is commonly used as a placeholder, similar to how we might also use “bar”, or combine them as “foo bar”). But if you follow the link and see the breach it was exposed in, you’ll see a very familiar name:

Which brings us to the next question:

How Do “Fake” Email Addresses End up in Real Websites?

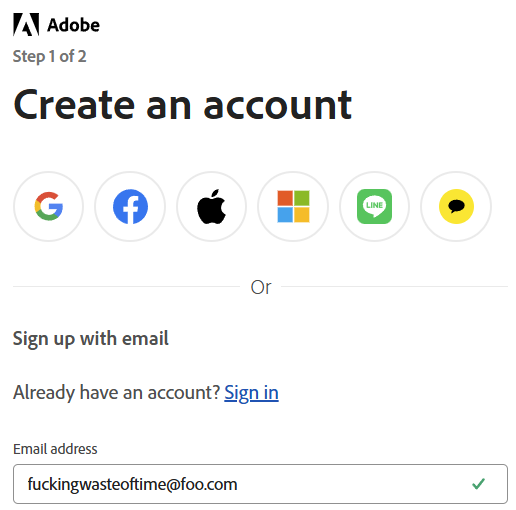

This is also going to seem profoundly simple when you see it. Here goes:

Any questions, Bruce? This is just as easily explainable as why we considered it a valid address and ingested it into HIBP: the email address has a valid structure. That is all. That’s how it got into Adobe, and that’s how it then flowed through into HIBP.

Ah, but shouldn’t Adobe verify the address? I mean, shouldn’t they send an email to the address along the lines of “Hey, are you sure you want to sign up for this service?” Yes, they should, but here’s the kicker: that doesn’t stop the email address from being added to their database in the first place! The way this normally works (and this is what we do with HIBP when you sign up for the free notification service) is you enter the email address, the system generates a random token, and then the two are saved together in the database. A link with the token is then emailed to the address and used to verify the user if they then follow that link. And if they don’t follow that link? We delete the email address if it hasn’t been verified within a few days, but evidently, Adobe doesn’t. Most services don’t, so here we are.

How Can I Be Really Sure Actual Fake Addresses Aren’t in HIBP?

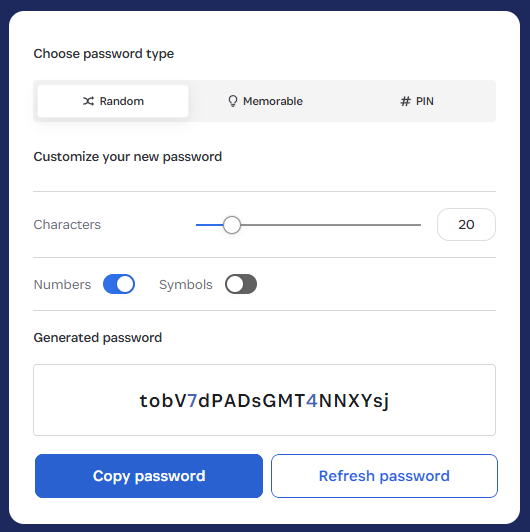

This is also going to seem profoundly obvious, but genuinely random email addresses (not “thisisfuckinguseless@”) won’t show up in HIBP. Want to test the theory? Try 1Password’s generator (yes, Bruce, they also sponsor HIBP):

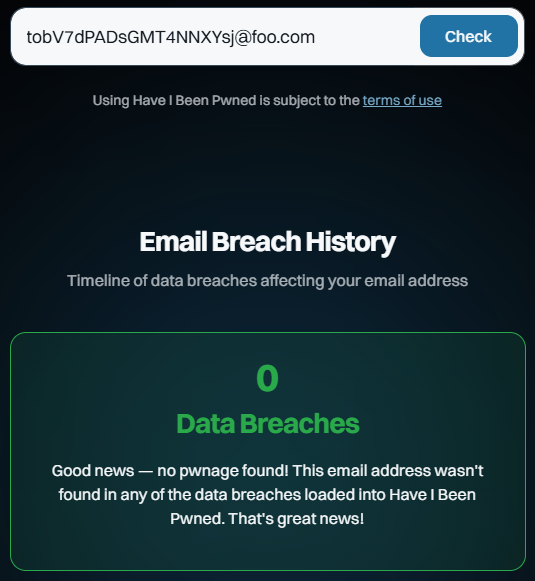

Now, whack that on the foo.com domain and do a search:

Huh, would you look at that? And you can keep doing that over and over again. You’ll get the same result because they are fabricated addresses that no one else has created or entered into a website that was subsequently breached, ipso facto proving they cannot appear in the dataset.

Conclusion

Today is HIBP’s 12th birthday, and I’ve taken particular issue with Bruce’s review because it calls into question the integrity with which I run this service. This is now the 218th blog post I’ve written about HIBP, and over the last dozen years, I’ve detailed everything from the architecture to the ethical considerations to how I verify breaches. It’s hard to imagine being any more transparent about how this service runs, and per the above, it’s very simple to disprove the Bruces of the world. If you’ve read this far and have an accurate, fact-based review you’d like to leave, that’d be awesome 😊